Is Western Yoga accessible?

by Jasmin Sweeney-May, GLYS Graduate, 2025

Today, there is a perception that yoga as currently practiced in the West, is the purview of a relatively small, niche population. My observations of the typical yoga profile, based on attending studios in London, Paris, Amsterdam, Berlin and Sydney, all four locations considered to be large, multicultural, metropolitan cities, is the typical participant at a vinyasa flow class is white, female, slim / slight of frame (size 4-8), flexible (often from dance or gymnastic backgrounds), aged between 25-35 and clad in LuluLemon or Sweaty Betty. This applies mainly to practitioners but also to teachers to a lesser extent. What factors might lie behind this skewed distribution, which is not representative of the local population? My view is that there are various barriers to entry; conditions either real or perceived that result in effectively excluding some groups from spaces where yoga is practiced. The exclusion can be both self imposed and imposed.

I may be biased as I belong to many underrepresented groups. I started my yoga journey 3 years ago as I approached my 51st birthday. I was menopausal, I was the heaviest I had ever been following 3 hip surgeries in the 3 previous year, I could not do the forms of exercise I had previously enjoyed. I am also neurospicy and blessed with melanin.

This essay considers what tangible and intangible barriers to entry may exist, how significant those barriers may be as possible root causes as to why other segments of the population may not perceive yoga as being accessible ‘for them’, and suggests actions that may help break down those barriers so that yoga becomes more inclusive. Much of what follows is based on my own observations and experiences but also the experiences of others I have encountered along the way.

Context

The yoga studio is where there is a concentration of this group. It can therefore be an intimidating space for those who perceive themselves not belonging to this group. This can be compounded if the studio atmosphere is not welcoming; teachers never ask your name, practitioners are very clique and don’t engage with newcomers or sometimes not even with each other.

What does accessible mean?

The Cambridge dictionary defines accessible as ‘being able to be used by everyone’. The two important words in that definition:

Able: capacity to do something. This is not linked to preference or comfort.

Everyone: which by definition is universal and so by default, it is fully inclusive.

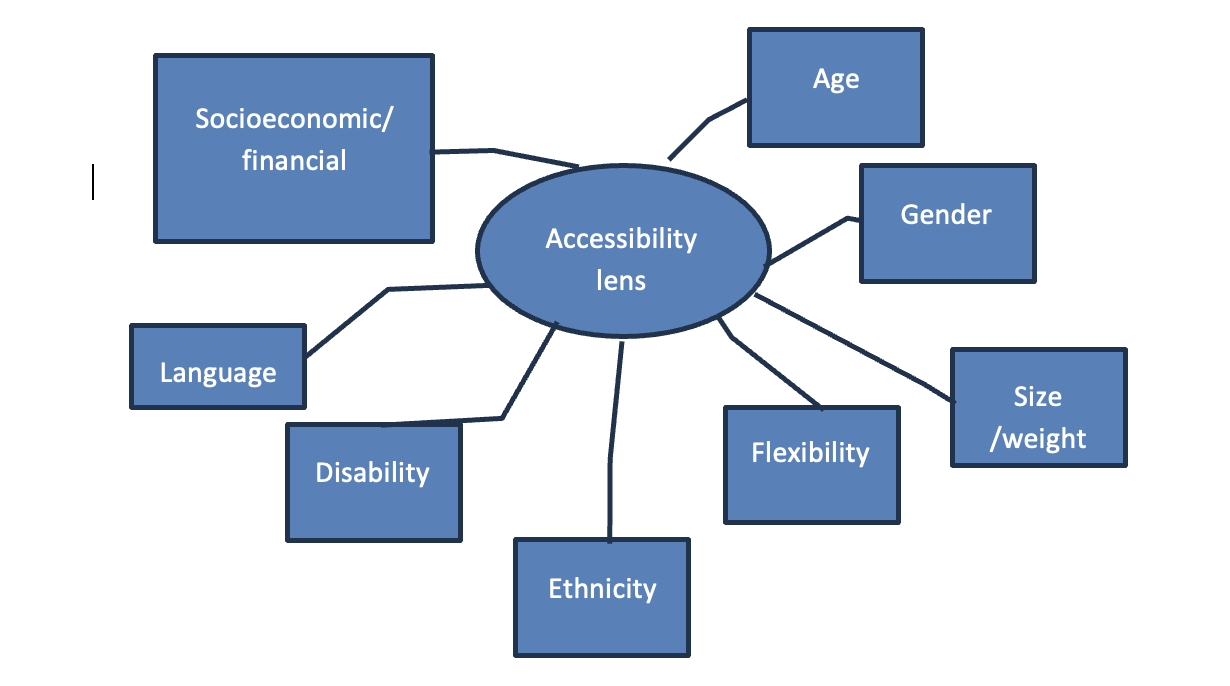

In current parlance, accessibility has multiple lenses, each of which has barriers to entry which may be tangible (I.e. quantifiable) or intangible (I.e. unquantifiable but perceived or experienced by people).

The Can’ts

There is a familiar refrain, one I have been guilty of using until I gave myself a strong talking to and virtual slap; “I can’t do yoga! I’m too old, I’m not flexible enough, I’m too big or heavy.”

These are examples of self imposed, intangible barriers to entry. They have more to do with an individual’s preferences, comfort zone and mindset than their actual ability to stand on a mat in tadhasana. However, if a person really does not want to even try yoga, they may cling to these “can’ts” as viable reasons for not even trying. Similarly, if an overweight woman in her fifties, somewhat inflexible, may feel uncomfortable at putting herself in a milieu where she will obviously stand out due to her age size and inability to do as the others do, the can’ts can readily become a shield behind which to hide and protect oneself from being exposed to others.

Are age, body size and flexibility really barriers to yoga being accessible? No, they are not. There are older yoga practitioners, larger practitioners and not all yogis can do splits or put a foot behind their heads. If these attributes themselves are not true impediments to practicing yoga, then it holds it is more about mindset and prevailing attitudes.

Age

Attitudes to ageing in general are changing. As Gen X, that wonderfully rogue generation that embraced quirky fashion in the 80s and partied hard in the 90’/00’s (many did not stop), look to age disgracefully, many have embraced various pastimes and forms of exercise. Those that tend to flourish have the ‘I don’t care what others think’ attitude. It may be genuine or it may be a façade. The important thing is it gets them moving and being active; focussed on what they are doing and how it makes them feel instead of being concerned about the judgment of strangers. This mindset shift is crucial in enabling people from outside the yoga norm to get on the mat. However, not everyone has that mindset or confidence. In perimenopausal women, for whom anxiety levels, self doubt increases while confidence decreases, having a welcoming and supportive space that encourages movement irrespective of age can be an important catalyst.

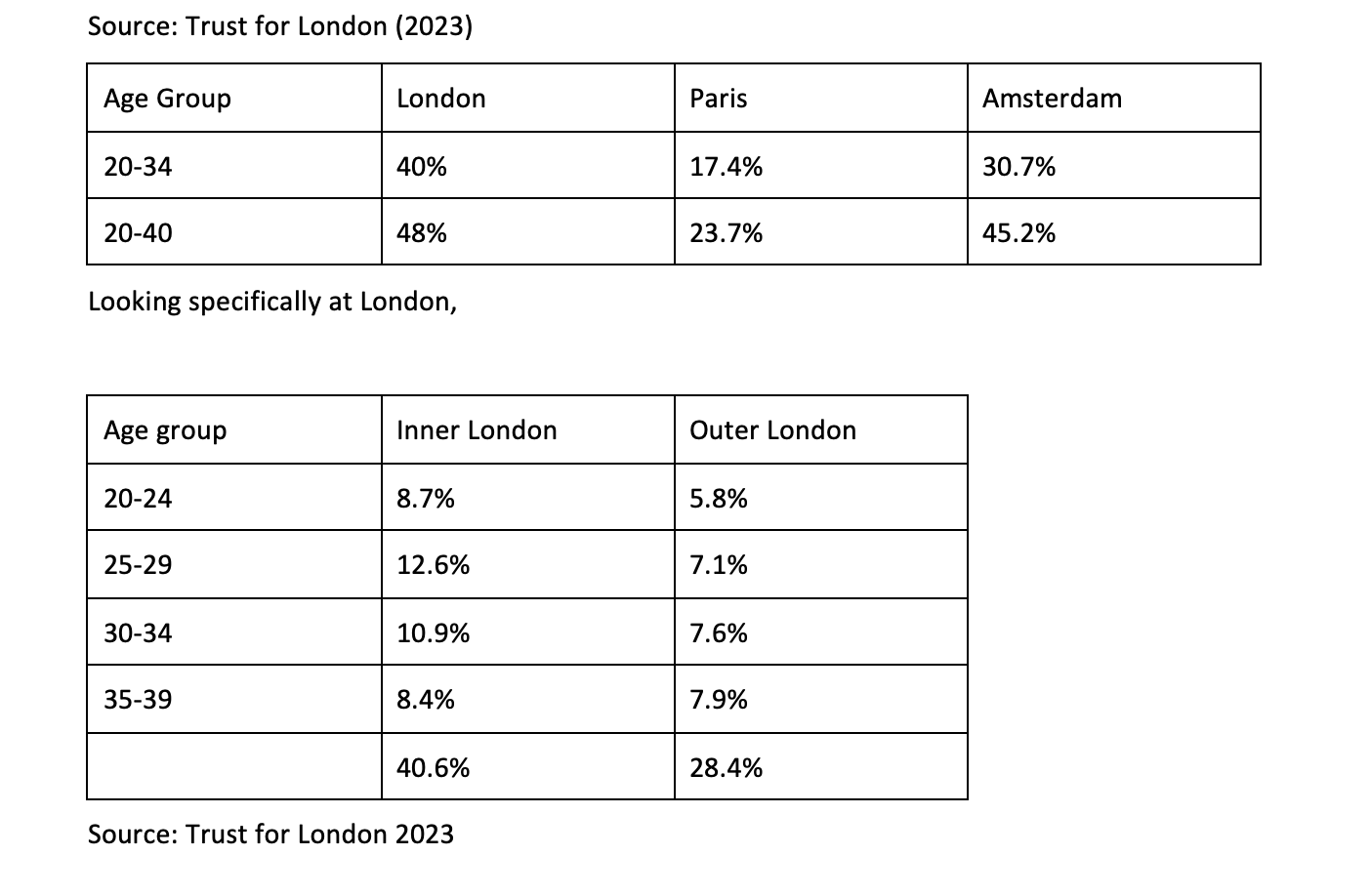

What do we see in the yoga studio and is this representative? Major cities such as London Paris and Amsterdam have larger populations of 20-40 year olds in the centre compared to the suburbs and compared to the national average.

My observations as a yoga tourist, courtesy of ClassPass, broadly reflects the age distribution above with some outliers.

- Dynamic classes in central studios typically have a younger demographic.

- Slower modalities, including Iyengar, appear to have a higher median age.

Indaba has a solid 20-40 cohort with a good number of over 40, 50 and 60 practitioners observed.

Mission has a core cohort mid 40s and under. Those in older age groups are underrepresented. I am typically one of the oldest people in any given class.

Outer London locations not only have yoga studios but other venues such as gyms and local spaces such as church halls. In the observed area (South East London*), I have observed of a higher proportion of aged 40+ practitioners, consistent with the age profile of the local demographic.

*Hot Yoga Brixton, Oru Space East Dulwich, YogaRise Peckham Rye, Renaissance Yoga Brockley, Kindred Yoga Deptford, Yoga House Catford, Soma Space Honor Oak, Breeze Yoga Beckenham.

Is there an offering for different age groups?

- Not observed on timetables of inner London studios where there is a lower median age in the local demographic and older practitioners going to these studios typically still have a strong practice and want to go to dynamic class as opposed to ‘yoga for seniors’.

- Observed yoga for seniors is typically offered where there is a larger ageing demographic. This tends to be a gentler form of yoga, sometimes chair based to provide for limited mobility issues in ageing population.

- Teen sessions? Only observed in outer London studios (Breeze and Yoga House Catford). Aim being to provide a safe environment for body conscious teenagers who may feel uncomfortable practicing near scantily clad, sweaty adults. NB: a significant proportion of teenage girls remove themselves from formal sports / exercise settings, so the lack of provision may be due to low demand.

Gender

Whether in a gym environment or in yoga studio, the majority of class practitioners are female. This may be because of various perceptions, including yoga being a soft form of physical exercise and so not attracting the men looking to develop strength through traditional strength training, safer environment for women (safety in numbers, not being hit on or leered at as happens in gyms, not being in testosterone heavy environments of weight training with men grunting as they look to push more weight). Conversely, yoga environments can feel very intimidating to men. I have observed that where there are one or maybe two men in a class, they often place themselves farthest away from the teacher and as much out of sight by the female majority (I.e. back of the class). This may be due to feelings of inadequacy if they are inexperienced practitioners. Some solo male practitioners place themselves nearer the front of the class. I once asked a male practitioner why he did so when most men go to the back. His reply, ‘I don’t want people thinking I’m here to gawk at ladies in leggings and bra tops whilst presenting their backsides in downward facing dog.’ #Me Too has left men feeling uncomfortable in majority female environments for fear of accusations of impropriety.

For aspiring or new practitioners in the LGBTQ+ community, the challenges faced in day to day life can be present in the yoga studio. While some studios have taken positive steps to declare themselves as LBGTQ+ friendly, embracing inclusive policies re the use of changing rooms etc, true inclusion will require changes in mindset, attitudes and behaviours so that LBGTQ+ practitioners feel included and safe. For example, a transgender man identifying as queer may feel unsafe using the changing room designated for those identifying as male. To quote one teacher ..’I would not feel safe changing post practice in the gents changing room and applying make up there. Given the day to day comments / reactions I get when going from A to B, I don’t need that s***. When I use the ladies changing room, no one bats an eye. They go about their business, treat me as one of the girls and pay me compliments on my makeup, which is always an ego boost!’.

Flexibility

There is a naturally occurring flexibility bias towards women which can make men feel less capable. Also, there appears to be an unconscious bias prizing flexibility. Many visible representations of yoga, from pictures of BKS Iyengar, asana series posters, practitioners on Instagram reinforce this bias, even if this is not the intention. To the average yogi, this can easily give the impression the purpose of a given pose is to go deeper, wider, lower. Unfortunately, the ego can then:

- dissuade the less flexible from trying yoga, when they are likely to benefit significantly, and

- drive the average yogi to push beyond their flexibility range, causing injury.

Disability

The physical practice of yoga benefits all bodies. Those with physical limitations may not believe the physical practice is available to them (cf flexibility above). Dedicated yoga studios will often have props such as bricks, bolsters etc to assist most physical limitations. The use of chairs is common in Iyengar yoga, enabling practitioners to access various poses with a higher level of support and experience poses in different ways. However, many studios do not have items such as chairs. Other spaces where yoga is practiced, such as gyms, church halls often do not have any props at all, effectively excluding those with physical limitations unless they bring their own portable props, such as blocks Those with physical limitations can feel further excluded when, instead of being taught in an inclusive manner, the direction from the yoga teacher may be to rest in child’s pose. While teaching a person with a physical limitation in an open level class of 30 practitioners will be challenging, especially if the person is new to your class and new to yoga, it can and does create a negative perception for the student. The perception that this is not teaching; it is being lazy and reinforces the bias in favour of able-bodied practitioners. My view is that is somewhat unfair if a teacher has been blindsided with a new student with a physical disability. Speaking to the student at the start of the class and again afterwards for a better understanding of their limitations, which poses they found difficult / painful and why will enable the teacher to troubleshoot and propose modifications for the next class. This makes the practice accessible and makes the student feel included. This is a real skill which, based on my own experience, may teachers either do not have, or do not feel confident in troubleshooting to make asana practice more accessible.

Ethnicity

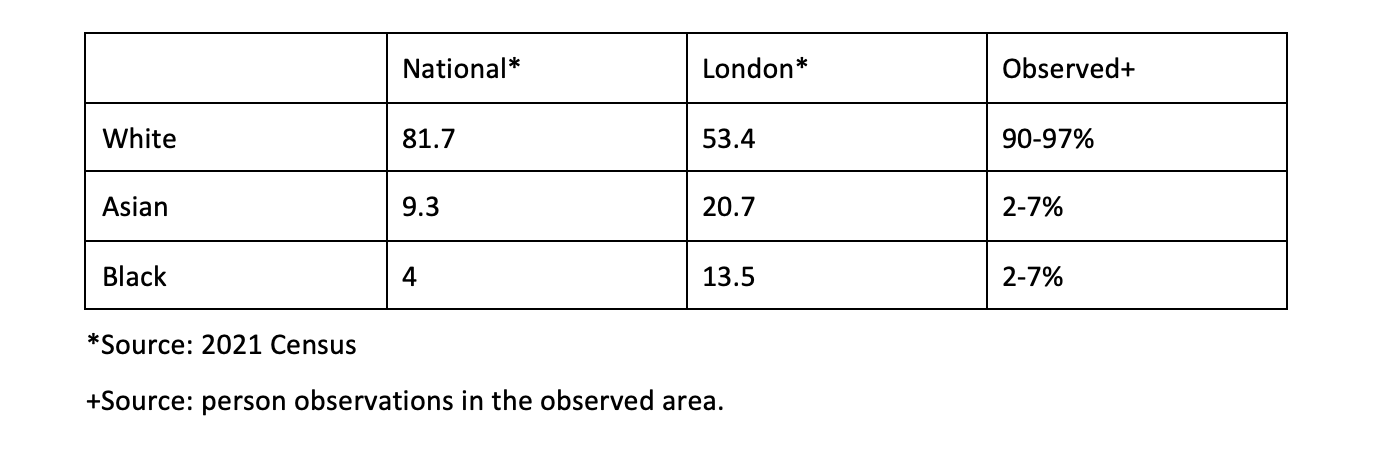

Yoga is an ancient tradition originating from the Indus Valley. In the last century, the physical practice of yoga was introduced to the west and has become increasingly popular. However, I continue to observe the obvious: physical yoga practice in common spaces is the preserve of white people. Whilst the white population remains the largest ethnic group nationally at 81.7%, followed by Asian (9.3%), Black (4%) and Mixed (2.9%), these national averages per the 2021 census present differently in large metropolitan cities such as London.

As to why ethnic minorities are underrepresented in the yoga class, the reasons may be varied. For some, they may feel yoga is not a past time with which they readily associate, having not seen other yoga practitioners or teachers who look like them. For others, if the are used to being surrounded by one ethnic group, they feel uncomfortable when they are in the minority. They can also feel uncomfortable where their body type differs from the average in the room, Eurocentric beauty norms, heightening feelings of discomfort and feeling othered. When intersected with gender, single gender ethnic group based classes create safe spaces which can encourage participation. This could explain why figures such as Louis Alcott have established male only yoga groups for men from the African diaspora or yoga classes for Muslim women. However, another reason for underrepresentation may be that ethnic minorities typically continue to be members of lower income groups. The cost of participation is a significant barrier to entry for many people.

Financial

The cost of yoga participation is high. Yoga studios are businesses. Rent, business rates, overheads and teachers all cost money. One of the few elements that are reasonably within the control of yoga studios are:

· how much they pay teachers,

· when to schedule classes to maximise revenue and

· how much they charge for drop in classes and memberships.

There is a range of drop in price structures, including at premium studios. While some studios have a flat pricing structure with no differentiation between peak / off peak, in studio / online classes, others do differentiate and charge more for in studio classes. Drop-in classes range from £15-£28 on average in London. Studios sometimes provide introductory offers (unlimited yoga for £x for y days), special offers during the year (Valentines day, Easter specials, Halloween, Black Friday sale, Christmas and New Year) and class packs. This is a great way to attract new visitors, get them hooked and to keep the cost down for them, however the lower prices are short lived. Membership costs are similarly expensive. At some of the central London studios, annual membership can reach £2300 and offer a slightly lower tariff with limited access for the more budget conscious yogi! These high rates are designed to cover the cost of running the studio, including paying experienced teachers a reasonable rate. While the principles behind this high cost and sliding rates may be laudable, namely having those who can afford to pay more to do so, so that those who are less able can still participate through means tested bursary programmes.

Attempts to make the cost more affordable exist by offering online classes at a lower rate, lower rates for younger age groups (only observed at one central London studio where 18-26 year olds pay 75% of the full tariff for unlimited access). One studio used to have an off peak membership which was designed to support those working close by to practice during off peak times (unlimited access between 0730 and 1730) for 25% of the full membership and rates for those on lower incomes. However, these lower rates are not widespread (off peak membership has disappeared) or are not at a level low enough to make a real difference. Steps to prove the low-income status to some studios may prove to be humiliating for the applicants, alienating them further. If the applicant is successful, the reduced rate can still represent more than 25% of weekly net income for someone on benefits, which remains a significant outlay. Further restrictions may be placed on these memberships, either restricting access to off peak times or excluding certain classes. This essentially means accessibility is conditional. Some well-meant initiatives are in place to make classes more affordable. These include community classes, typically taught by new graduates, are the most affordable classes, typically priced at £5-£7 for in person classes. These classes tend to be during off peak times when most people work or may have childcare obligations which may limit the take up. Some teachers hosting online classes go a step further and operate an honesty pricing structure of ‘pay what you can’. This encourages those who can afford to pay more to do so, so that those who cannot afford more can pay less. Whilst most people these days possess smartphones, if they do not, then online classes require a suitable device.

Additional costs may be incurred. This could be the clothes worn, which are expensive if keeping to main, popular brands such as LuluLemon or Sweaty Betty. These outfits are not necessary but may be preferable to foster a sense of belonging. Another cost is the mat. Mats are often available for free in some studios whereas many studios charge a fee (£2-£4) for mat hire. Good quality, grippy mats are expensive (£80-140 when on sale) and can cost as much as £175 at full price and with attractive design or personalisation.

Conclusion

Yoga in the west is not fully accessible in my opinion. Affordability is the main barrier to entry. It is a tangible, quantifiable barrier which limits participation in yoga in group settings. It reinforces the perception that yoga is within the means of those with higher incomes. In doing so, it effectively excludes lower socio-economic groups which may have a higher proportion of underrepresented groups. Reducing the cost of yoga will be difficult if the yoga studio model does not change. Yoga teachers, for whom teaching is more of a hobby, may be in a position to charge less for classes. However, this runs the risk of undermining the value of classes taught by teachers for whom teaching is their primary source of income.

The other barriers are intangible. There can not be quantified, only perceived. This does not negate the importance of these barriers. Creating safe spaces for underrepresented groups in all dimensions could increase participation where affordability is not the main concern. This would undermine the yogic principle of unity. Where mindsets are unable to shift, people will continue to feel uncomfortable in yoga environments.

For those who hold space in the yoga community, either as teachers, volunteers at studios or regular practitioners, we have a role to play. It starts with recognising the journey some people need to take just to show up on the mat in a group setting. Recognising where they are and what their needs may be. This requires lifting the veil of ignorance and educating ourselves on other peoples’ experiences. Changing the atmosphere at yoga studios may go a long way to changing mindsets. Let’s move away from the yoga studio being a place to practice to a community space, something between the home and a temple. You welcome people to your home or temple. If more teachers and studio members were welcoming of new attendees, it would go a long way to making everyone feel valued members of the community.